Review: The War of the Worlds, by H.G. Wells

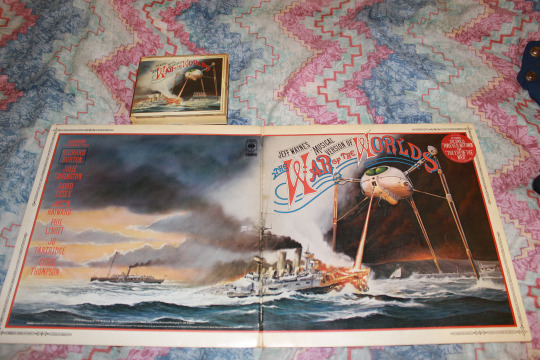

Yes, my first exposure to this

story as a child was Jeff Wayne’s rock opera musical version. Then the 1950’s George Pal movie, and… well,

I’d seen and heard just about every adaptation of this story (including the

infamous Orsen Welles radio broadcast that allegedly caused mass panic in New

York), before finally getting around to reading the original alien invasion

story that they were all based on.

Almost all of Wells’ famous

sci-fi works – War of the Worlds, Invisible Man, The Time Machine – were written

in a quite short period in the 1890’s, but are by far his most remembered

works. Whereas Verne was a renowned

futurist and wrote a great deal of early engineering and technology porn, Wells

background was in biology and that shows a little in his writing. In War of the Worlds, for example, he’s obviously

far more interested in the Martians themselves and the evolution of life on an

alien world than he is in all their war machines. In Verne’s story ‘From Earth to the Moon’, he

obviously did a lot of research and spent a lot of time describing how we might

get there. In Wells’ ‘First Men in the

Moon’, how they get there obviously didn’t matter so much to him as exploring another

world and encountering its strange new creatures. It’s a much more exciting story which no

doubt helped to really popularise the genre.

While The War of the Worlds might

be the most famous alien invasion, it was definitely not the first future

war/invasion tale. During the Napoleonic

Wars, the French general had first proposed a Channel Tunnel as a means to

invade England, and even had plans drawn up for it. By the later half of the nineteenth, Germany

was also becoming an industrial power in mainland Europe. With new technologies being developed, the

British began to sense that their position as a global power was tenuous and

lived in constant fear of invasion. In

1871 a story appeared in entitled The Battle of Dorking, told from the

perspective of an old soldier in the future recounting an invasion of Britain

from Germany. This was followed by other

accounts of future war, such as Albert Robida’s ‘War in the 20th Century’,

that proposed the use of tanks, aerial bombardment, and chemical and germ

warfare. In the future, many believed,

it would be whoever had the most advanced industry technology that would win

wars. And then H.G Wells stepped in and

proposed the ultimate threat, penning perhaps one of the best opening

paragraphs ever to a novel:

‘No one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century

that this world was being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater

than man’s and yet as mortal as his own; that as men busied themselves about

their various concerns they were scrutinised and studied, perhaps almost as

narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinise the transient creatures

that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacency men went

to and fro over this globe about their little affairs, serene in their

assurance of their empire over matter. It is possible that the infusoria under

the microscope do the same. No one gave a thought to the older worlds of space

as sources of human danger, or thought of them only to dismiss the idea of life

upon them as impossible or improbable. It is curious to recall some of the

mental habits of those departed days. At most terrestrial men fancied there

might be other men upon Mars, perhaps inferior to themselves and ready to

welcome a missionary enterprise. Yet across the gulf of space, minds that are

to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast

and cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly

and surely drew their plans against us…’

At this point however I would

like to point out that the title of the story is misleading. It’s not so much a ‘War of the Worlds’ as it

is just Mars versus England. At least as

far as we know from the story, they never land anywhere else. The story, an account of the invasion, is

told from the point of view of a nameless journalist in Woking at the time the

first Martian cylinder lands nearby (although there is a diversion as he also

relates what happened to his brother who was caught up in the flight from

London after the war had begun).

After initial attempts to

establish contact fail after the Martians unleash their heat-ray burning Earth’s

ambassadors to a crisp, and half the nearby village, the army is called in while

the Journalist gets his family to safety.

But he then goes back, for some reason which I’m sure must have seemed

important at the time, only to find the Martians have emerged from their

cylinder in huge mechanical tripods and annihilated the human forces arranged

to contain them. The Journalist is then

just swept along as the Martians make their way north toward London, and

although the British to succeed in destroying a few war machines, ultimately

the superior technology and weapons of the Martians prevails and they rout

everything in front of them. In addition

to the heat-ray, they unleash a gas simply referred to as ‘black smoke’ that

chokes the life out of everything in front of them. The journalist witnesses a couple of battles,

but then becomes trapped in a cellar with an increasingly erratic Parson after another

cylinder lands on his house, where he witnesses the vampiric nature of the

aliens as they suck the blood from human’s they’ve captured.

And then, after defeating

everything thrown at them and winning the war, the Martians just… die. According to the narrator, killed by the one

thing they hadn’t counted on – bacteria.

If you remember from the Verne story I looked at, in the nineteenth

century it seemed a number of people believed that in the future we would

eliminate all bacteria and thus do away with illness. The Martians, being more advanced, had

already done that and so had no immunity to micro-organisms. Yes, it seems silly to us now as we know that

bacteria can’t really all be killed and it wouldn’t be a good idea to do so

even if we could. But Wells’ had to end

the story with Martians beaten not by anything humanity had thrown at them, as

to do otherwise would defeat the point that no matter how powerful we think we

are, the universe is a huge and there’s always going to be something out there

that can kick our ass. It is worth

noting however that everything about the Martians and what happened to them is

merely speculation on the narrator’s part as no-one is ever able to talk or

communicate with the aliens directly.

Some view this story as in fact

being a satire of The British Empire and colonialism, and there are certainly

passages to suggest that. Especially at

the beginning of the book where the narrator discusses the treatment of native

peoples by the British, and the fates of the many colonists who succumbed to diseases

they had no immunity to (of course it more often happened the other way round,

with Europeans bringing over diseases native people had no immunity to). But indeed to this day, fear of alien

invasion really stems from how human beings have treated each other in the

past.

All that aside, if you’re a

sci-fi fan you obviously have to read this book as it’s the original alien

invasion, and like Jules Verne collections of Wells’ works are today usually available

in book and e-book forms at a quite low price.

Also, if there’s ever a chance again for you to see the rock opera

version, do so – it’s effing awesome.

Leave a Reply